• Former U.N. undersecretary Anwarul Chowdhury will deliver a keynote speech about United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 at the Nov. 14 symposium, hosted by The Bush School of Government and Public Service’s Program on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS)

• “WPS is about national and global security, plain and simple. I’m honored that the Bush School is a fulcrum for WPS under the leadership of Dr. Valerie Hudson.” – Bush School Dean John B. Sherman ’92

BRYAN/COLLEGE STATION, TX (Oct. 29, 2025) – UNSCR 1325 is probably among the most important declarations that most people have never heard of.

The United Nations resolution mandated that all sides of a conflict put measures in place to prevent harm to women, particularly sexual violence, during military operations. It codified the notion that women must have a role equal to that of men in deliberations about war and peace, especially during peace negotiations and post-conflict reconstruction. And if that seems like an obvious requirement now, and perhaps should have been obvious in 2000, when UNSCR 1325 was passed, Valerie Hudson, Ph.D. would like to offer two reminders: The resolution required the support of many powerful men. And it passed only a few years after international courts finally declared – for the first time in history – that rape is a war crime.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, as it is formally known, “didn’t happen all that long ago,” said Hudson, director of the Bush School’s Program on Women, Peace, and Security. “But it was a revolutionary idea at the time.”

To Hudson, the fact that such a declaration is still recent is more reason to celebrate its passage. The Bush School will do that Nov. 14, when the 11th Annual Texas Symposium on Women, Peace, and Security will examine the enduring legacy of UNSCR 1325 on the 25th anniversary of its passage. Speakers will include retired Bangladeshi ambassador Anwarul Chowdhury, an influential champion of global peace and the president of the Security Council when the resolution was passed.

“We should not forget,” Chowdhury famously said in a 2005 speech, “that when women are marginalized, there is little chance of an open and participatory society.”

“TRAINED IN THREAT ASSESSMENT”

The Program on Women, Peace, and Security is premised on a simple, thoroughly studied proposition: what you do to your women, you do to your nation. Conversely, the more secure women are, the more secure the nation is. Hudson can provide numerous anecdotes and reams of research demonstrating that when militaries and intelligence agencies incorporate the perspectives, knowledge and skill sets of women, they are more effective.

Hudson can also put it more plainly: “The idea that half of the population is vital to national security is not some hare-brained notion. National security is equally the concern of women.”

Women’s value in national security is partly due to a few simple demographic realities: without women, there is literally no future for the nation; women are as invested in the defense of the homeland as men; and including women means doubling the pool of potential candidates, making more top minds available. But women also bring a different shared set of skills and experiences, Hudson said. The difference is not biological but rather that women are socialized to become security experts by, for example, recognizing and responding to threats, she said.

She is fond of an anecdote from the Women In Intelligence conference last year at Texas A&M. Gina Bennet, a retired CIA intelligence officer (and author of the “National Security Mom” book series), told the audience about how, when she was new to the agency, she was posted abroad to learn how to operate in dangerous environments. She compared notes with a young male colleague. What was the most surprising thing he learned? His reply: that when you get into a car, the first thing you should do is lock the door. Bennett paused to let the anecdote sink in among the mostly female audience. Chuckles spread.

“Every woman knows that the first thing you do when you get in a car is lock the door,” Hudson said. “Women face security issues every day of their lives. Do I go for a jog at night? Can I walk home alone? Women are trained in threat assessment from the time they are young children by virtue of being women.”

“YOU’RE MORE LIKELY TO SUCCEED”

Allison Bendersky first heard Hudson speak a little over a year ago, in a crowded orientation room, days before starting Bush School classes. Bendersky knew nothing about Hudson, UNSCR 1325 or the Program on Women, Peace, and Security – but she was so moved by Hudson’s presentation that she decided to pursue that degree concentration. She is now president of the Women, Peace, and Security Student Organization, which is open to all students and has an unofficial membership count of around 60.

They see many of the same things in the program as Bush School Dean John B. Sherman ’92, a career intelligence official who was (among other posts) chief information officer for the Department of Defense. The program, Sherman said, “Is about national and global security, plain and simple. It is imperative that we include the perspectives, expertise, and experiences of women to ensure we can prevent wars, keep the peace and, if necessary, defeat adversaries.”

Bendersky can cite numerous statistics to bolster an unbroken succession of reasons for women’s inclusion in national security. She said women should pursue such careers partly to ensure that what she calls the “WPS program point of view” suffuses the halls of power. She said that such influence is a necessary check on abuses that arise when, as has been consistently demonstrated, around one-third of college-age men admit they would force a woman to have sex if faced with no consequences. Bendersky also said women should join the profession partly because studies show that the more empowered a country’s women are – and few professions offer more power than national security – the more stable and peaceful those countries are. Peace talks go better and the subsequent peace is more durable when women play a meaningful role at the negotiating table.

Bendersky points to Liberia as a place where this dynamic unfolded in obvious, nation-shaping fashion. In the early 2000s, the West African country was plagued by more than a decade of civil war. Armed bands of rebels (including child soldiers) roamed the countryside looting and killing. Government surveys conducted after the violence ended found that more than 90% of women experienced sexual violence. Rape was employed as a wartime tactic.

The revolution that brought the violence to an end started with a mother of five struggling to keep her family alive. Laymah Gbowee organized a church prayer session to beseech God to end the violence. During the session, Gbowee recruited other women to protest the violence. The protests grew into a movement that spread among Christian congregations, then to Islamic women rallied by Muslim police officer Asatu Bah Kenneth. The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, as it came to be known, proclaimed that a bullet did not distinguish between faiths and drew thousands of protesters to rallies. Galvanized groups of women pressured religious leaders, who in turn pressed Liberian warlords and then-president (and former warlord) Charles Taylor for peace talks. Those eventually happened in neighboring Ghana – and when they verged on failure, hundreds of women locked arms around the hotel in which the men were negotiating, physically blocking the exits and daring security teams to arrest them. The women threatened to strip naked, leveraging a cultural taboo under which the act was a particularly wicked curse on a man. Thus, the warlords and the president were forced to reach a peace agreement. Gbowee won the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts.

The women had prevailed by essentially inviting themselves to the negotiating table. They did this at a time when UNSCR 1325 had just declared, in essence, that women not only have a right to a seat at the negotiating table but that they must be heard. The Liberian movement proved that, like the resolution states, “when you have women involved in peace, you’re more likely to succeed,” Bendersky said.

Freedom House now considers Liberia a stable (if still troubled) nation. It is generally considered among Africa’s least belligerent countries. In 2006, its people elected the continent’s first woman president. Which leads Bendersky to one more statistic, learned from Hudson: for every 5% increase in women serving in a nation’s parliament, that nation’s government is nearly five times less likely to use violence.

“THE LOGIC OF CONFLICT”

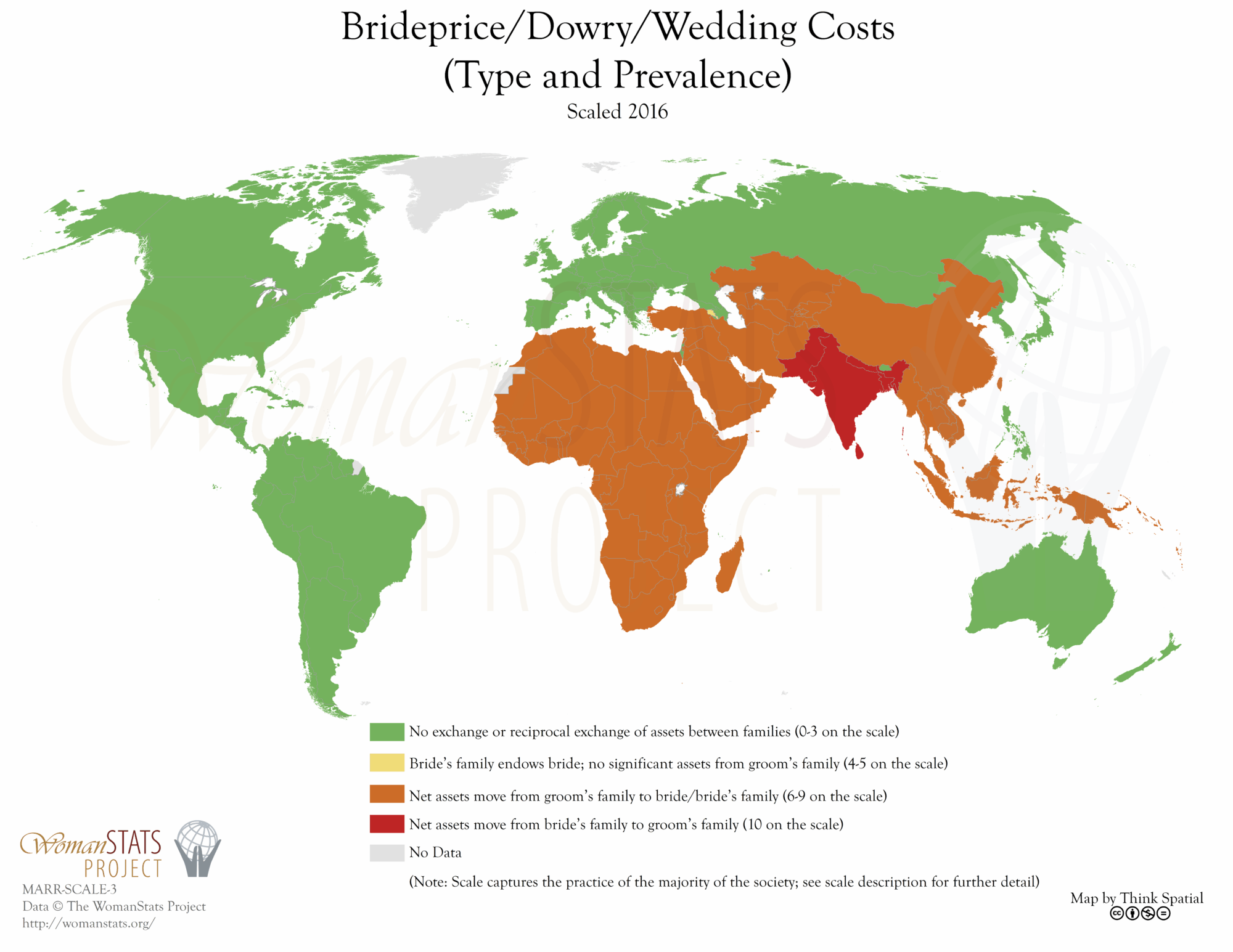

In 2017, Hudson and fellow researcher Hilary Matfess, Ph.D., published an article in the academic journal International Security about how rising brideprice fuels violent conflict. About three-quarters of the world’s population lives in places where families require payment from prospective husbands in exchange for permission to marry a daughter. In such societies, a man’s social status is directly tied to his marriage status. But rising prices can push marriage beyond a young man’s means. When that happens, rebels and terror groups often offer to pay brideprice, or even provide brides, for recruits.

Brideprice is common in Afghanistan. The United States military was still operating there when the article was published and, about a month later, Hudson received an email from a U.S. State Department official. He wrote that a few weeks earlier, a delegation of tribal elders from near Pashtun territory approached him and other U.S. officials with a warning: wedding costs were rising. The writer said that he commiserated about how lavish and expensive weddings had become in the United States. But he dismissed the idea that Afghan wedding prices were a U.S. government concern. Only after reading Hudson’s article, he wrote, did he realize that the elders were warning him that rising prices were pushing young men to join the Taliban. The official said he wished he had not dismissed the elders’ concerns, adding, as Hudson recalls: “They were trying to help us.”

Such male/female dynamics set off ripple effects that often cause armed conflict and should therefore be closely monitored, according to Hudson and Matfess’s examination – but that is not happening, probably because analysts “too often (consider) ‘soft’ social issues a lower priority.”

“Marriage, with all of its associations with women and family, perhaps seems to those in these circles to be a far cry from the logic of conflict,” according to the article. That logic stems from a traditionally male-informed perspective, and women are less likely to dismiss family patterns, the article states; women see connections that others may miss, Hudson said.

By way of example, Hudson points to the hunt for Osama bin Laden. It was a mostly female CIA team that discovered the hiding place that Navy SEALS raided to kill him. The team’s breakthrough? Analyzing intelligence on the domestic help at the house in which bin Laden was living.

“THE ROLE THAT WOMEN HAVE BEEN PLAYING”

Hudson can inspire crowds. And she oversees a program shaped partly by an aspirational goal: helping to close the opportunity gap between men and women in an important field, thereby making nations more secure.

But Hudson does not speak aspirationally. She considers herself a national security realist. She tends to describe not what women could do if incorporated into the United States military during overseas conflicts, but what they did do during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Cultural mores discouraged women in those countries from mingling publicly with men, particularly U.S. military personnel. So female U.S. engagement teams talked with Iraqi and Afghan women, gaining key intelligence, such as where the women would not allow their children to play, thereby gleaning the location of homemade bombs hidden by U.S. adversaries. Hudson similarly describes how the Australian military incorporated female advisors in its response to a tsunami. Those advisors counseled commanders to not make assumptions based only on what the surviving men would need, but also to account for the needs of the women – some of whom would be pregnant and close to giving birth, all of whom would be at risk if housed in group tents absent security to stop prowling men. Hudson describes how the CIA team of mostly women found bin Laden.

Hudson and her colleagues have analyzed the underlying data and reached a clear conclusion.

“Women are essential in securing the nation,” she said. “Women’s knowledge, perspectives, and skill sets have made, and make, their nations more secure.”

Chowdhury, the keynote speaker at the upcoming conference, speaks in similar terms. He was Bangladesh’s representative to the United Nations at a time when Bangladesh held the presidency of the U.N. Security Council. He pushed for UNSCR 1325’s passage as part of a long, distinguished career championing the rights of women and children. He called for the vote on UNSCR 1325. And in a documentary about the importance of the resolution, he did not say that the Security Council recognized “the role that women can play.” Or “the role that women should play.” Or even “the role that women have a right to play.”

He said of the historic vote: “The Security Council recognized, for the first time, the role that women have been playing.”

###

IF YOU GO:

What: 11th Annual Texas Symposium on Women, Peace, and Security

Where: Annenberg Presidential Conference Center

When: Nov. 14, 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Who:

• Valerie Hudson, Ph.D., university distinguished professor and director of the Bush School’s Program on Women, Peace, and Security

• Retired ambassador Anwarul K. Chowdhury, former undersecretary of the United Nations; initiator of UNSCR 1325 and founder of the Global Movement for The Culture of Peace.

• Tanya Henderson, president and founder, Mina’s List

• Kayla McGill, cofounder, WPS Collective; former senior policy advisor, U.S. Department of State Secretary’s Office of Global Women’s Issues

• Saira Yamin, Ph.D., distinguished WPS practitioner and academic